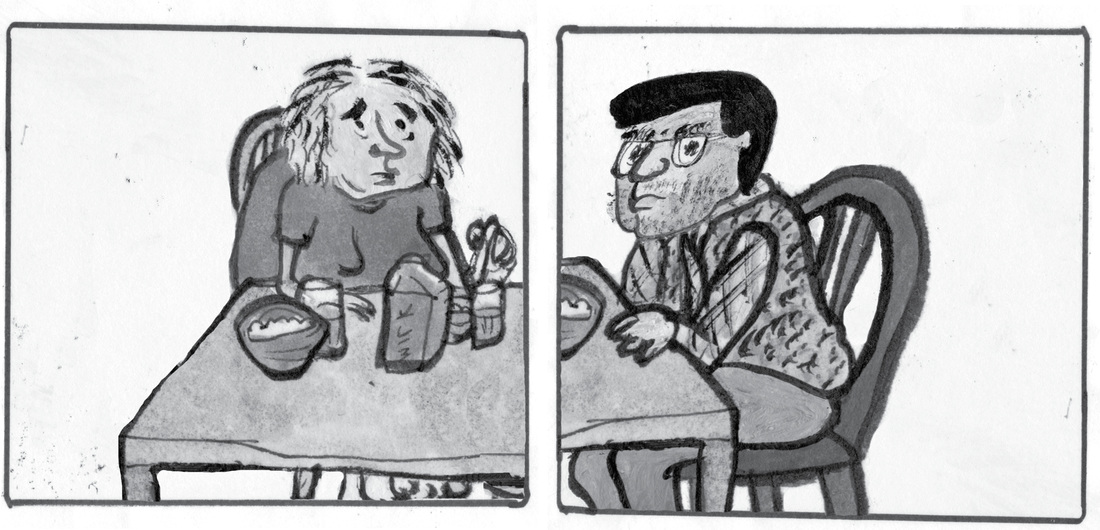

IT'S SUNDAY AND BETSY AND PHIL,

former biological parents of Slave and current adoptive parents of the Infanta, are entitled to a day off like anybody else.

They take their breakfast together, not speaking, just as Slave and Eye are setting about their lesson next door, in a house that is for some reason, legitimate or less-than, unreachable to them, off-limits.

They sit and regard one another, each planning a separate day, though each is equally bound to stew in Sunday’s familiar mix of shame, boredom, and cautious hope.

|

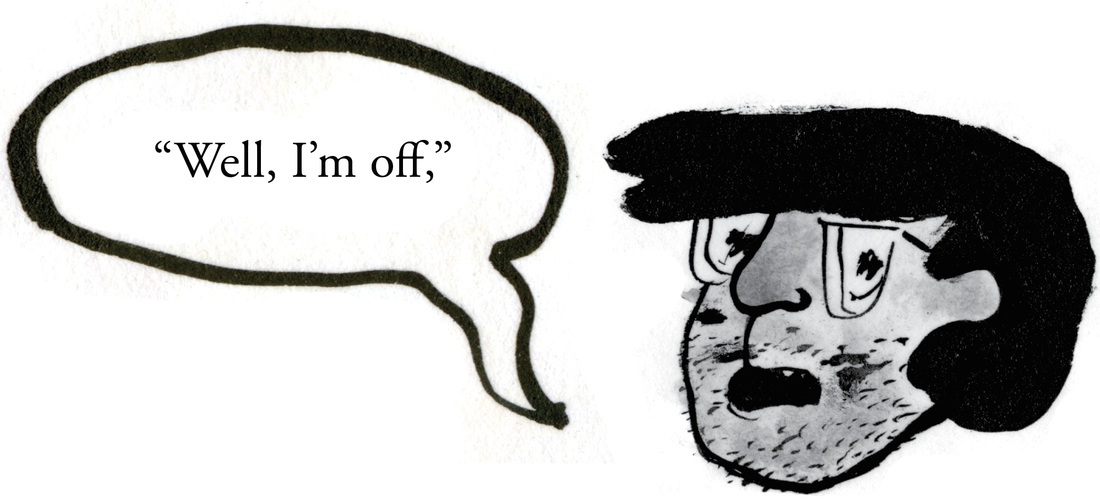

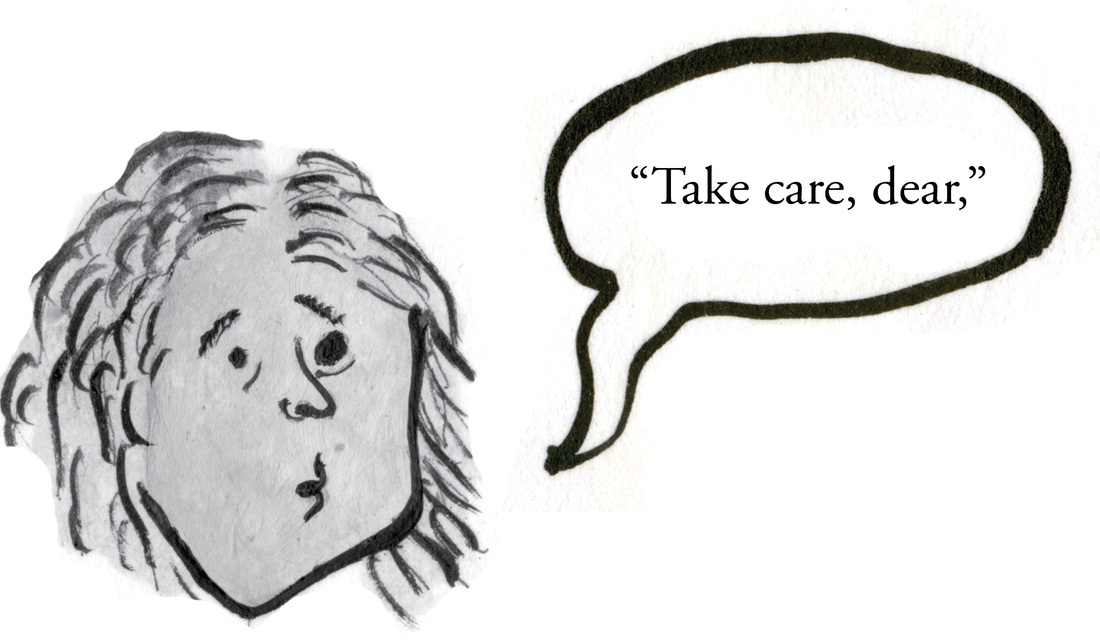

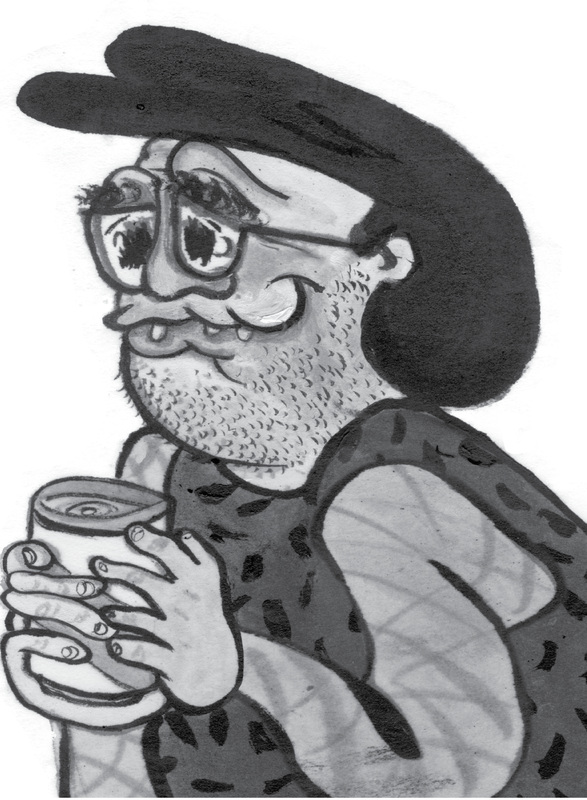

says Phil, a beat sooner than expected, discovering that his shoes are already on and his vest – it’s hot out, as always, but it feels good to don a scrap of outerwear upon exiting the indoors – is easily within reach. |

I wonder where she thinks I’m off to, thinks Phil, a bit manic as he makes his way out the door. I wonder what story I’ll tell her today.

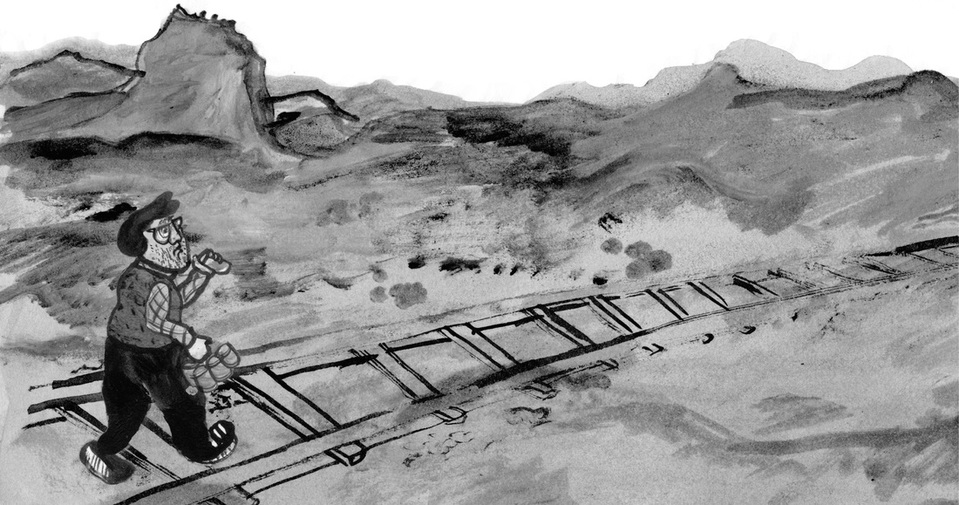

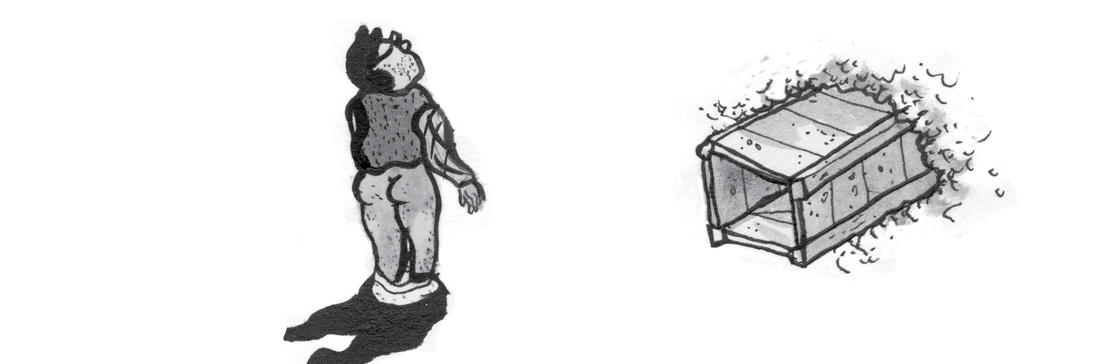

SOON HE'S AT THE TRAIN TRACKS

He walks along, drinking his first beer, kicking Magic cards, socks, hair, and baby teeth. What a cliché about the tracks being littered with used condoms, he thinks, as he’s thought before. No one seems to use them around here.

A stoat or weasel regards him from a hole and he looks away from it, toward the first oncoming train, on his second beer.

A stoat or weasel regards him from a hole and he looks away from it, toward the first oncoming train, on his second beer.

AFTER A WHILE,

snatches of old-time blues rattling in his head, he reaches his destination: a small wooden box dug into the gravel hillside, just past the railroad bridge, where the tracks flatten out and begin to turn north.

He finishes his fourth beer pissing in the weeds, his belt and the top of his Levi’s unbuttoned, hiding the last two cans under some roots further back.

He finishes his fourth beer pissing in the weeds, his belt and the top of his Levi’s unbuttoned, hiding the last two cans under some roots further back.

He sighs, watching a worm sink into the earth, and falls to his hands and knees, crawling headfirst into the wooden box he built out here when his son went missing.

When he’s finished, he lets his Levi’s fall the rest of the way and pulls his cotton boxers down with them, squinting up at the sun, gauging how hot it’s going to get. The hotter the better.

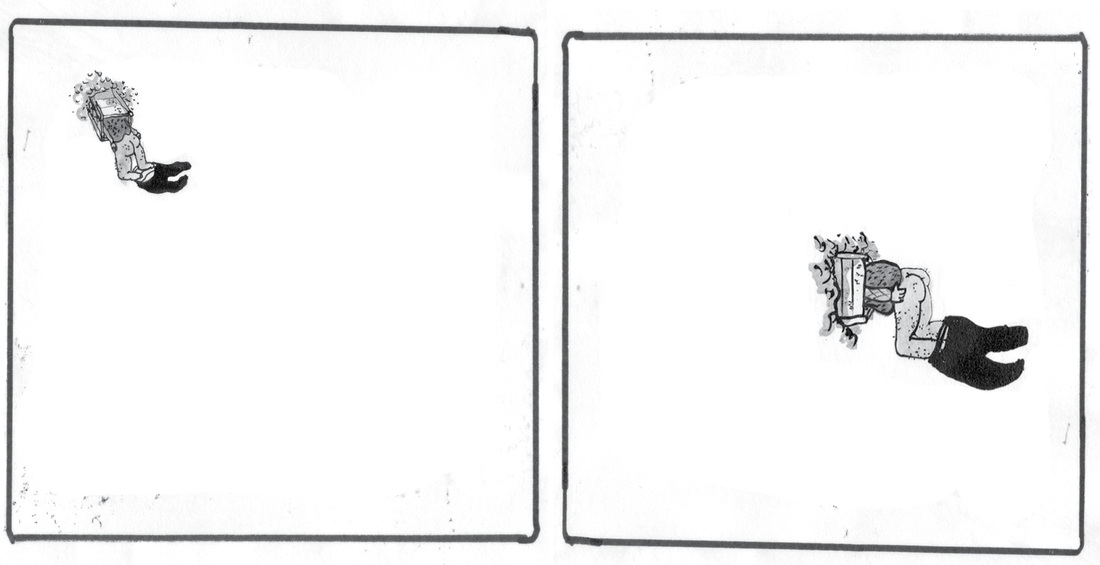

IT ABSORBS HIM

up to his shoulders, fitting snug with his arms pinned to his sides, leaving the rest of him exposed. He straightens his back and stretches his thighs so his knees are at a right angle to the ground, his ass fully exposed to the day and the passing trains, no part of it hidden.

|

Though he cannot reach his hands that far back, he tries to use the muscles of his upper thighs and lower back to spread the cheeks as wide as they’ll go, feeling the first of the day’s flies settle in for a landing.

Such is my penance, he begins to think, taking his time with the words, since there are not many of them and a great many hours to fill. Such is my penance for losing my son … for allowing him to be taken and finding there was nothing I could, or wanted to, do about it. He feels dumb, oftentimes, for spelling it out so literally, as if he didn’t by now know what happened and how he felt about it, but he can appreciate the value of ritual, of saying things you already know again and again only for the sake of saying them. So he says it again, out loud this time, feeling the hot inside of the box echo: Such is my penance for … |

THE SMALL ECHO

of his voice is trumped by the giant echo of the train, hurtling off the bridge and around the bend. He pushes his ass out, feeling it swell, imagining the passengers watching from the windows, jeering at him, thinking, That there is a fool, a doomed man.

Though he cannot hear them through the train’s thick sealed windows, he feels the intensity of their derision, all of it deserved, mixed with the intensity of the sun beating down.

TIME PASSESThe day’s middle comes and goes.

NOW SOMEONEis sitting beside him. Always, around this time, someone comes.

He’s never known who it is, nor ever permitted himself to wonder. It’s part of his penance, another feature of the ritual, this exposure and nearby humiliation, in contrast to the more distant passing of the trains. |

Good, he thinks. Look at me, whoever you are. See me like this.

IT'S HIS WIFE

Betsy.

She’s the one, and always has been. Such is her penance, her part to play.

She’s never told him, and believes he genuinely doesn’t know.

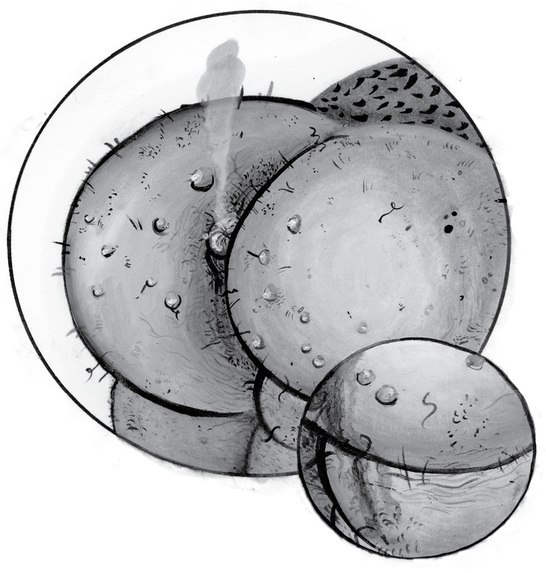

She has a picnic basket with a turkey sandwich and a chocolate bar open beside her, and a magnifying glass in her hand.

She takes her time, eating, watching the trains, enjoying the day.

She’s never told him, and believes he genuinely doesn’t know.

She has a picnic basket with a turkey sandwich and a chocolate bar open beside her, and a magnifying glass in her hand.

She takes her time, eating, watching the trains, enjoying the day.

|

Then, before the sun gets too low, she sighs, stands up, brushes away crumbs, and takes her position behind her husband.

She holds the magnifying glass right up to him, focusing it directly on his anus, staring hard through it, refusing to look away, thinking, This is what I deserve, what I must do, for losing my son, for … |

She recites this all silently while her husband recites it out loud inside the box.

He moans as the sun through the glass begins to burn him, and she watches the tender protected skin sizzle and pucker, welts and boils beginning to form. Some blood-like substance begins to run, drying on the hairs of his inner thighs.

THANKFULLY, a train chugs by just then, drowning out the worst of his noise.

When it’s gone, she removes the glass. Enough for today. She likes to believe that the burn pattern on her husband’s skin resembles the shape of their son, a sign from on high that they are doing the right thing, atoning in the proper manner. She wipes the glass with a towel from her picnic basket, though she knows it has not touched flesh. When the sun has most of the way set, Phil stands up, biting his lower lip to keep from whimpering any louder than necessary. |

He dabs at his rear and legs with a roll of toilet paper he keeps in the wooden box, then pulls up his Levi’s and boxers, brushing gravel from his knees, and waddles gingerly away, back to where he hid his last two beers.

|