DREAMTIME'S OVER

Last night’s dose has gone cold and subtle.

Slave stands over Eye in his big bed, preparing to

Slave stands over Eye in his big bed, preparing to

MILK HIM.

Eye lazes, rolling side to side, hiding from the morning through the window, delighting in how it singes his tender lid.

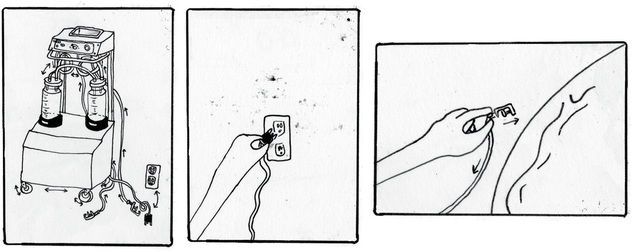

Slave looks away to yawn. Working by touch like a cadet who can assemble his gun blindfolded, he screws together the pumps and tubes of

EYE'S MILKING MACHINE.

He clamps the Machine onto one of Eye’s four dream-filled nerves, twisting it tight.

Eye groans in a way that Slave has, with the advent of his own puberty, begun to find indecent; Slave pretends not to hear.

He clips a vial onto the Machine’s far end and activates the Pump.

Eye groans again as Dream Milk begins to flow.

THE MORNING RITUAL COMMENCES.It gets very bright outside; the night has left no smudge.

When the first vial is full, Slave swaps in the next one, clamping the Machine onto the next nerve. When all four vials are full, Slave takes them down to the freezer, labels them with the night’s date and dosage info, and puts them in their place, among all the Milk of Eye’s previous dreaming. |

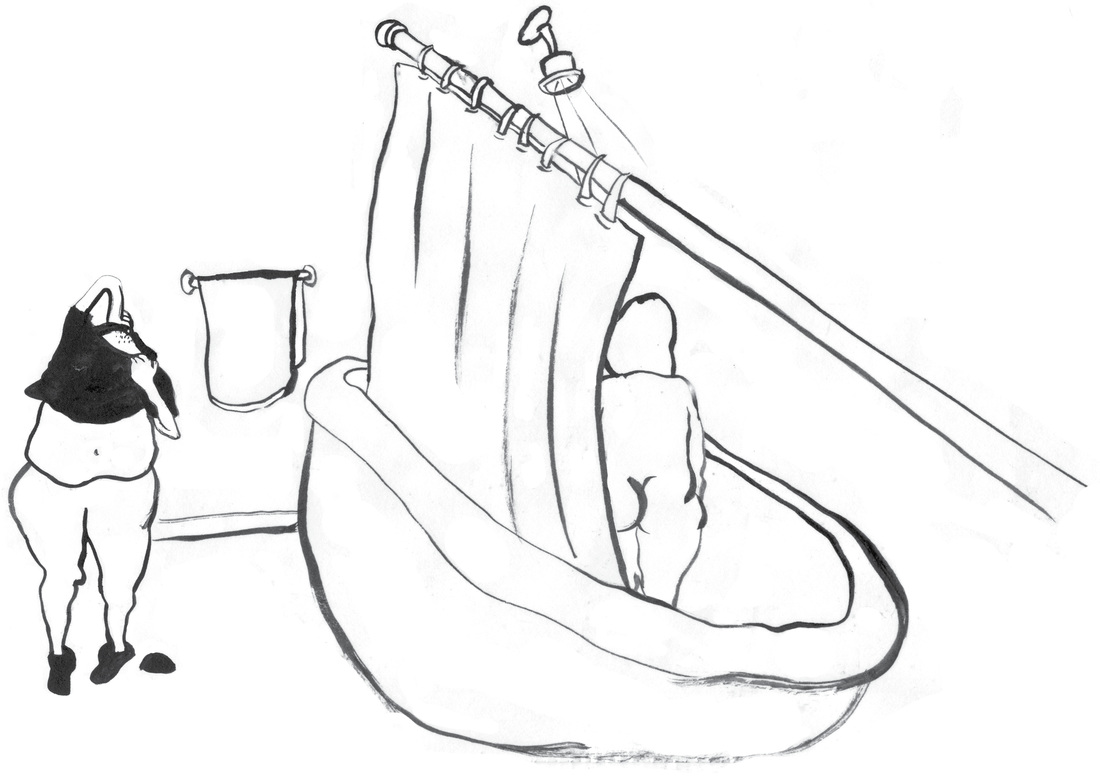

A QUICK SHOWER

while Eye prepares the Day’s Lesson.

|

Slave stands under the water and regards himself with more curiosity than shame, as if each day the form of his body takes him freshly by surprise. There is something, he reflects, that I find impossible to remember about me.

Afterwards, standing before himself in the antique mirror – this step is new – he sneaks a dab of Eye’s pricey European Shaving Cream, flush with rosehips and cashews, and spreads it over the three hairs on his upper lip, the four on his chin. Holding his breath, he slices with Eye’s straight razor. |

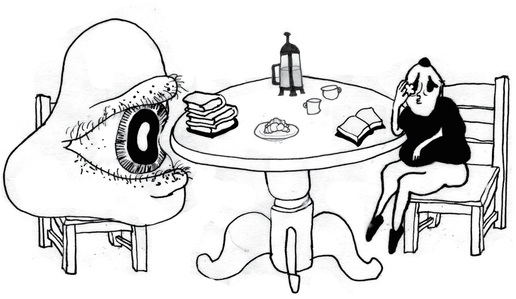

Slave appears before Eye at the downstairs Lesson Table, in his best clothes, a little blood-dizzy, a wad of paper stuck in that place, a few drops already seasoning his collar.

|

With French Press coffee and croissants set out – Eye provides breakfast on Lesson Days – the Day’s Lesson, on conflicting approaches to naming “the God behind God,” begins.

Slave tries to listen, holding his pen above its notepad, but a warm breeze makes a claim on his attention. Looking toward its source, Slave is greeted by something unexpected: |

THE FRONT DOOR IS OPEN.

He is reminded of the end of last night’s dream, when he came in that way after parting with the Infanta, whom he almost kissed … not for the first time, he wonders what link there must be between the dream and the state he’s in now.

Soon, his only thought is:

Soon, his only thought is:

THE FRONT DOOR IS OPEN.

As Eye holds forth on superfluous angels and heretical nicknames, Slave begins to imagine leaving.

There’s a soaring elation, a surge of unlimited power. He imagines himself whooshing across profound distances, taking great cities by storm.

But, as on times before, his vision here grows hazy. It’s as though the haze forms the natural border of how far out he can go, a storm marking the edges of his purview, blotting out all progress a minute into his imaginings.

Thus the Vision of Escape becomes tainted and Slave feels confused and desperate, grasping at straws, uncertain what to make of his life now that he’s struck out on his own.

He’s on some road far from the one he started on, in some place he cannot navigate because he can barely imagine it.

There’s loneliness, homesickness. And hunger, exhaustion, filth. How he longs for a shower.

The vision becomes nothing but haze, and then the haze breaks and he’s back on the street outside Eye’s house, and that of his parents, next door.

But, he’s now become a very, very old man, stooped over in loose suspenders and a sweat-stained shirt he can’t afford to replace or even launder, leaning on a cane, shuffling through the dust, coughing into a handkerchief.

He’s spent his life, it seems, wandering in circles, and has at last made it back where he started.

He approaches Eye’s house as a traveling salesman, a battered knapsack hanging heavily from his shoulders, scanning the yard for dogs.

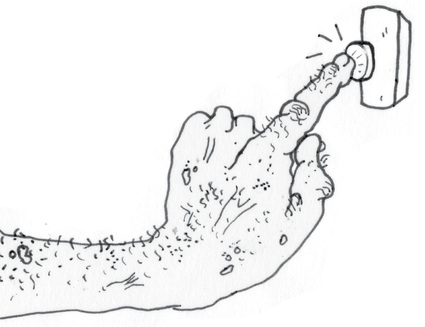

He leans his cane against the front door and, with a twisted, leathery finger, rings the bell.

HE WAITS AND WAITS,

his life dwindling toward its end.

At last, the door opens and he is greeted by a young boy, healthy and cheerful.

“Yes?” the boy asks.

Old-Slave is struck by the resemblance, but he cannot be sure. Is that me? he asks himself. Or just another like me?

Am I really that replaceable?

“Yes?” the boy asks.

Old-Slave is struck by the resemblance, but he cannot be sure. Is that me? he asks himself. Or just another like me?

Am I really that replaceable?

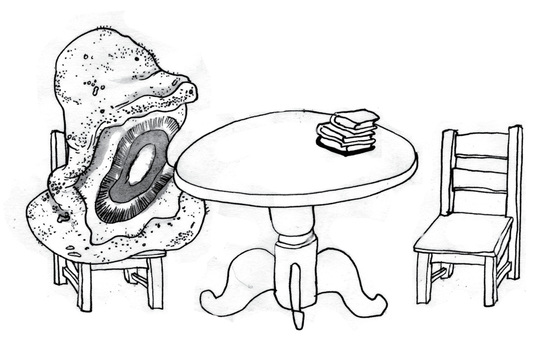

Behind the boy he sees Eye, sitting at the kitchen table with his Lesson Books out.

Eye, too, is heartbreakingly old – his nerves are gray and droop like busted elastic, his lashes have fallen out, his once-vivid white is now so clouded he looks blind.

“Excuse me,” whimpers Slave, peeling the paper from his bloody lip and dabbing his eyes with it.

He leaves the table and closes the front door, locks it, then returns, ready for the rest of the day to begin.